|

Post author Maggie is a former resident of MRH who has graduated college and passed her board exam for social work. Her writing has been edited for clarity. In 2015, I graduated high school from inside My Refuge House (MRH). I was homeschooled there with only 3 others in the same year as myself. I was so excited to graduate and was looking forward to getting out of the shelter. At only 17 years old, I was naïve and only thinking about having fun. However, I understood my chances of returning home at that time were small because I was told I would only be released once I was 18. Looking Toward the Future The social workers at that time were Ate Rose Ann and Ate Megs. Ate Rose Ann is now the Director of Program Operations. We had a weekly check-in, where she would ask me about how I was doing inside the house, if I had any problems, and how I was coping with everything. Close to my graduation date, I told Ate Rose Ann about what my plans would be upon returning home. Of course, I only told her the good things, like finding a scholarship for college, and helping my mom and dad, hoping that she would let me go home early. Ate Rose Ann let me talk and then told me the shelter planned to offer a college scholarship opportunity to their graduating students. I went through the weeks-long interviews and the application process to get the scholarship.  I always wanted to finish schooling but I never really thought about college. I did not know what course of study to take or what I was good at. My first choice of study was psychology and my second was social work. Everyday, I prayed to God about what course I should take, knowing it would take me four years to finish it, plus a board exam. I did not want to make a mistake in choosing because in the long run, I wanted to be happy with my studies, and avoid wasting my time. I prayed hard and decided on social work. Starting College for Social Work On my first day in college, I was overwhelmed with emotions. I was excited, nervous, and happy. I didn't know what to expect - everything was so fast that I felt like I needed to sit down and breathe. I was with Dolores, my best friend, and we were both very happy that we had the same classes and schedules. I depended on her emotionally because I was shy and did not really know how to make friends with new people as I was adjusting to my new environment and new setup. One of my favorite subjects was Social Deviation because it teaches that people do something bad or out of the norm not just because it is in their personality, but also because of problems, trauma, and stress. My professor made the discussion fun and very interactive. I was not always a good student. I would cut classes, and there was even one subject I never attended. During different classes I would always hear other students saying that the professor was a terror teacher, and that she would ask each student to stand up in front of the class and memorize our national song, but she would not let you sing it, you had to relay it as a poem. I was shocked and afraid of what I heard even though I was still not able to see her face to face. I wanted to drop out of the subject and take it another semester, but I was missed the deadline. The whole semester I was enrolled with it and never once did I attend her class. Friendships During weekends, I had a 3-hour Saturday class with the NSTP (National Service Training Program). After class, Dolores and I would go to malls for window shopping and sometimes to eat at Jollibee, or to see movies if we have extra money from our allowance. Everything was fine, until Dolores stopped going to class. She had made friends with someone I didn't know and I was left hanging. I wanted to stop going to school because I was shy without Dolores. I wondered why Dolores wouldn’t invite me to go with her when I told her that I would also skip classes. Later on, she told me that she was seeing someone, and that is why she decided to stop schooling. I tried so hard to convince her to go back to school. I even threatened that I would also leave school, but she said that I could make it without her, and that I have to get out of my comfort zone and start making new friends. She had already made up her mind, so I continued my studies since the semester was ending in just a month. Dolores made friends with someone else from school and introduced me to them. I grabbed the opportunity to say hi to them again without Dolores, and they asked me to have lunch with them. I was shocked and a little shy but I agreed to lunch. I was stoked and could not believe that I was able to mingle with other people without Dolores being there with me. My college life was fun again. I would go out with friends to drink and party, although it was against what MRH taught, but I felt like I would miss out if I didn’t experience those things in life. On weekends, I would go to a club with my college professors and friends. We would drink and dance all night. Although I partied a lot, I always tried to be responsible with my actions and only drink with people I trusted. I wouldn’t drink until I passed out, and I always knew my limit. The house parents and social worker in MRH were very concerned with my behavior because I would stay out past my 10PM curfew. They decided to let me stay in a dormitory inside the campus. I was so happy and, felt like I had all the freedom away from the rules and regulations inside MRH. It was hard at first, especially learning how to budget my allowance. Sometimes my allowance would run out and I would have to borrow money from my close college friends or my ex-boyfriend. In March 2020, I was about to graduate from college. I was excited but at the same time nervous. What would my life be like after college? This was the only question that I couldn’t seem to get off my mind. I had to somehow find a job while doing my review for the board exam in order to help my family who were financially struggling. It was the start of the pandemic and everything was canceled, including the board exam review and examination. Graduating During the Pandemic Lockdown During this time, the corona virus was already affecting Cebu, and lockdown was announced. I decided to pack up my things and go home to spend time with my family. We lived in a small two-story house with only one bathroom and bedroom. My parents, 5 siblings, and 3 nieces all lived in the house. I was hoping I could make up for the time I had been gone, especially for my mom. People were panic buying and hoarding stuff they needed for survival. My family struggled to meet their needs everyday and could barely afford to stock a few items or food for a week or month. We depended on relief goods from the government and non-government organizations. I saw my parents' struggles and frustrations. I became disappointed at myself for not being able to help them. Supporting My Family I started to look for jobs online. I sent out my resumes to a lot of BPO (business process outsourcing) companies and was rejected many times, but I did not give up, and kept thinking of my family’s situation. I was finally accepted in one of the biggest BPO companies in Cebu. I was happy and relieved thinking of being able to help my mother financially. I worked during the night from 10 in the evening until 7 in the morning. It was hard for me to adjust my sleeping pattern but I was able to cope with it and I made a lot of friends in my workplace. I worked there for a year, and during those times I tried to take the board exam. I struggled to find a balance with work and study, reviewing at least one to five pages a day from my book before enrolling for online review. I told my team leader that I would leave for a week and she was supportive of me. The Social Work Board Exam During my review, I would get distracted by my phone. Most of the time I found myself holding my phone, scrolling on Facebook and sometimes watching funny videos on TikTok. I felt guilty whenever I did that and I would talk to God and say sorry that I couldn’t focus. I thought that God might not let me pass the board exam, so I would leave my phone with my friend during the day and get it back at night, which was effective for me. The first day of the exam went well. The night before examination day, I was not able to sleep properly because I was so nervous. I woke up at 5 in the morning and went early to the school, without eating my breakfast. There were 5 subjects to take with 100 items each. I checked the questions I remembered in the questionnaire after the exam. During the exam, I got sad and worried because I thought my answers were wrong. On the second day someone from our examination room tested positive for Covid 19. We all went through the health protocol so we were not really worried - I tested negative. After a week, the results of the board exam were out. I tried to search for the results on my phone but I was so nervous that my hands were shaking and I felt like my heart was about to explode. Then, Ate Jam sent me a message saying congrats and I was so happy to know I made it. I shouted and jumped and then I cried because I could not believe it! It was a roller coaster ride for me. After the result of the exam, I looked for a job related to social work. I searched online and found an assistant job in an NGO. Although I would not be a social worker, I pursued it for experience. Currently I work with kids who are living in the street. We do psychosocial activities with them, oversee their problems, and help them to find solutions. I am happy with my work but the salary is not competitive enough to sustain my needs and my family. I cannot give the same amount I gave to my mom when I was working in the BPO, so I have been searching for another job again. I found a few jobs which I am hoping to receive good offers from. Without a sufficient salary offer, I will work in the BPO industry again so I can help my family, especially now that my dad is sick. I am hopeful that I can find a job that I will be happy with and that pays well enough to sustain our needs. I know that I can make it through this phase in my life. There is always a reason we experience things in life. Romans 8:18; For I reckon that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory which shall be revealed in us. I believe that every pain shall pass and it will be rewarded. Always trust in the Lord and cling to His promise.

0 Comments

Note: Charie is a family member of one of the young women we’ve been following for The Long Rescue. She’s 24 years old, living in Cebu, Philippines with her husband and two young children. I asked her to write a description of her life during the pandemic and how they are surviving after the devastation of Typhoon Odette. She wrote in her native language, Bisaya. Gladys David translated, and I have lightly edited for clarity. Photos and videos are also contributed by Charie. (Charie is not her real name, and pseudonyms are used throughout to protect the identities of Charie’s family members. ) -Jennifer Huang By Charie Our life as a family before the typhoon was difficult, but we were able to cope with problems and challenges. I already have two kids and am six months pregnant now. My husband, Mikel, works to feed us all. He also supports his siblings. We are living at his aunt’s house. Our day-to-day lives are hard due to the pandemic. Mikel’s business is what we have been depending on; he makes cockfighting spurs for roosters. Work has been very slow to the point where we barely had anything to eat. I have to bring my daughter for a checkup almost every month due to her asthma. She is always coughing, perhaps also due to the place where we are staying. The surrounding area is very dusty since we live at a carpentry shop, and Mikel’s business is also dusty and creates fumes. We struggle to buy food and pay for electricity and water, even more so if our kids get sick. At this time, we are looking for a house where we can live since our current place is about to get demolished. Unfortunately it’s very hard to find housing. I fear that our expenses will increase while we are renting, plus electricity and water bills, our food everyday, and my husband is the only one who has work out of all of us. We have no one else to depend on, we don’t have parents we can turn to. My mother is far from me since she was imprisoned (drugs), and I grew up without a father. When Mikel was 16 his father passed away and he became the breadwinner of his family. He continues to support our children, some of his ten siblings, and sometimes four of my siblings as well. We’ve cared for as many as eight children since I started living with him when I was sixteen. His mother is far away in Bantayan since she remarried, so it has been hard that there’s no one to guide us but we were able to cope. We entrust everything to God and we always pray. It would have been okay to not have parents to guide me because I have my siblings around me. My younger brother and two younger sisters were living with us, after our grandma kicked them out when they reached fourth grade. But not anymore. I am happy because they are in a place for a better future -- they went back to living with our grandmother. I miss them so much. But I am not on good terms with my grandmother, and we haven't spoken for several years. I would be happy to have my big sister, Dolores, around. Before, she was always there for me when I needed her -- and when she needed me I was there for her. But things changed the day she lost her beloved husband to Covid on August 24, 2020. After that day happened, she started changing her life. She is not thinking straight anymore and is acting irrationally. I feel so sad for her, and especially for Rosamie, her three-year-old daughter. Dolores has been leaving Rosamie here with me. She goes somewhere she doesn’t come back for several days, even a week. I always beg her to stop that and focus on her child’s future but she doesn’t listen to me. She used to be my super big sister, my best friend, but she changed.

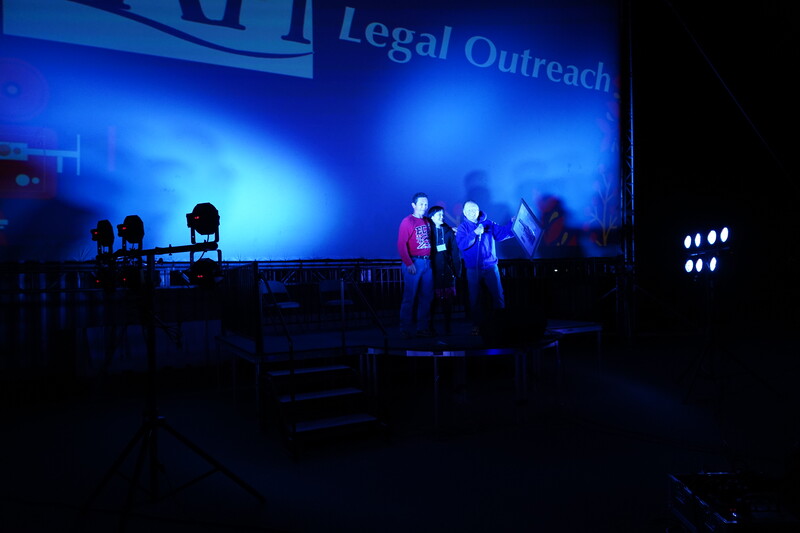

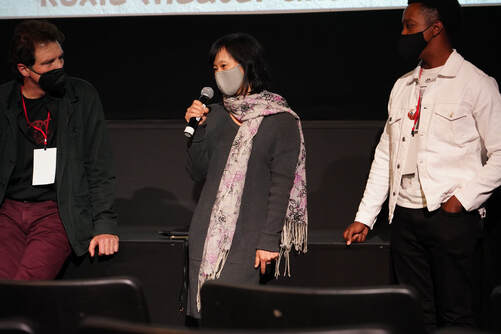

Even though she’s like that I still love her. I want what’s best for her and I miss her very much. I just hope and pray she comes back to be a better big sister Dolores someday. To read how Charie and her young family survived the destruction of Typhoon Odette on Dec. 17, please return to the blog next week, Dec 24, 2022, or follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter. November 6, 2021, This Adventure Called California found it's biggest screen ever, at The Lark Drive-in, in Corte Madera. Hosted by Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach, the annual fundraiser also featured art and poetry from local students, music videos by artists Ian Santillano and J.O.W.Y, and leadership and activism awards to Allan Low and the Vietnamese American Community Center of the East Bay. Everyone enjoyed massive bento boxes and popcorn in their cars, and settled down for the show. Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach, or APILO, is an incredible local organization that helped Arnoldo in the aftermath of trafficking. They helped guide him through several legal obstacle courses, including testifying against his trafficker, getting access to immediate aid like food and health care, and helped him get a lawyer to apply for his Green Card. Clearly, their scope goes beyond the API community, and they have many Spanish speakers on staff! In addition to its human trafficking program, APILO also helps low-income clients with legal issues with housing and eviction, provides training and legal services for elder abuse, and provides immigration services and education, free of charge. They also have a team providing legal help and resources to women experiencing violence, and have a youth outreach program to provide assistance to young people with immigration and gender-based violence issues, as well as social services. I have rarely worked with an organization where every single person is intelligent, conscientious, effective and drama free. But that's exactly what happened with APILO. They clearly have created a workplace full of dedicated people who are there to make a difference in people's lives, full stop. If you are interested in providing real support to vulnerable, hardworking people who are struggling in the Bay Area, please support this hardworking team HERE. Epilogue: After all that APILO has done to support This Adventure Called California, I certainly didn't expect anything more. But they gifted me with this original serigraph of Heart Mountain Internment Camp by Richard Tokeshi. As Dean Ito Taylor, APILO's executive director said, the work symbolizes "our quest for justice." Amen. Not only is the image haunting and beautiful in it's own right, but it's especially meaningful because my husband Doug's parents were also interned during WWII, at Topaz. Having this work on my wall will be an inspiration when my computer crashes or I'm afraid to make that phone call, or I just get discouraged from the daily grind. Thank you, APILO, for an extraordinary night, and for all of your incredible service you provide to our community. More photos of the big night! And for those of you who made it to the very end, a bit of gratuitous self aggrandizement... Because the honking horns was such a singular, unexpected life moment, that I wanted to share it. I hope all documentary filmmakers can have a film at a drive-in! Bigger and Bigger Screens Even though I've worked in documentary for ahem, going on 2 decades, last Friday was the first time I've seen my work as a director on the big screen. And today, I found out that This Adventure Called California won the Jury Prize for best documentary! To be honest, when I've seen other films with premieres and festival laurels, I didn't know if that would ever happen for my films. I've heard stories of films that don't get into any festivals, and based on my strikeouts on grant applications, I haven't found myself beloved by gatekeepers. And maybe this is our first and last festival, who knows? So we're gonna suck the marrow out of this win! (I'm gonna eat some mochi ice cream tonight!) We also had a very positive review! Including the line, "it's a lovely film." I've had to tell myself over and over again that it's not about getting awards and approval, so now I don't know how to feel! Mostly grateful, and hopeful that this might mean that people might actually want to watch the film. You can read the review for yourself here. This Adventure was screened with a slate of other Bay Area films, we got to meet other local filmmakers --mostly narrative, which was really fun. And this was a great warmup for next month's very big screen, a drive in! Rather than rely on festivals and gatekeepers, I'm working on an impact campaign --working with organizations and groups that can use This Adventure to support their work. In this case, anti-trafficking advocates, survivor service providers, labor unions, industry leaders working against exploitation, anyone who supports fair wages, fair trade, and workers' rights. If you know anyone like that who would be interested in our film, please send them my way! And come out to the drive in! Who knew we'd be on such a big screen!

The small cluster of workers, men, waiting outside of Home Depot. The dishwashers in the back of the restaurant that you sometimes glimpse on the way to the bathroom. The invisible hands that placed those ripe, red strawberries into the basket in your fridge, those neat yellow stitches on the pockets of your jeans. How often do we think about these people, who toil in heat, haste and exhaustion –on a good day – to make our lives more convenient, more delicious, and more affordable? Until recently, I was blissfully ignorant of the exploitation and pain that cushions my comfortable life. But then I met Jimmy Lopez, and I can no longer shop for deals without considering the human cost of my consumption. And then I met Arnoldo. Like so many, Arnoldo Lopez Contreras came to the US believing the promises of a recruiter –he would work hard, yes, but he would make great money. He could send money home to repair his damaged relationship with his daughter, maybe even convince his ex-wife to take him back. But that's not what happened. Arnoldo shares his story in my upcoming documentary, This Adventure Called California. Filmed from 2019 - 2021, it follows his emotional journey as he tries to rebuild his life and reconcile with his family, still contending with the aftermath of trauma, but also receiving unexpected generosity.

Arnoldo was one of an estimated 20 million people who live in forced labor conditions, ie, labor trafficking. I learned about labor trafficking doing research for The Long Rescue, and I realized that although it's more ubiquitous, it gets far less attention than sex trafficking. And unlike sex trafficking, which is hidden out of sight for many of us (though that's possibly because we're not be paying attention), our homes are filled products that likely contain exploitation in their history. Rare earth metals, or even nickel in electronic gadgets, chocolate, fast fashion, produce, all of these industries are known, documented to be rife with wage theft, unpaid overtime, child labor, debt bondage, or straight up slavery. But as journalist Noy Thrupkaew said in her incredible Ted Talk, “We are all implicated in this problem. But that means we are all also part of its solution.” I hope that when people understand the human cost of low prices, they learn to think twice, investigate the situation, choose companies that are transparent about their labor practices, who open their factories to third party inspectors. I hope we all think twice when hiring, ask questions when sourcing suppliers for our companies, demand compliance with Fair Trade standards the way we opt for organic food. It's not easy to be a conscientious consumer these days, I know, but every little bit helps towards building a collective movement that can change millions of lives. This Friday, July 30, 2021, join me in observing World Day Against Trafficking in Persons. You can catch a first glimpse of an excerpt of This Adventure Called California by followup us on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram, or signing up for our newsletter here. Thanks for caring about the people who make our products, and thanks for joining in the fight.  Early morning at Casa de Arnoldo Early morning at Casa de Arnoldo A few months ago, Arnoldo told me that someone had stopped by his truck and helped him fill out his US Census forms. "That's good, right?" he asked. "Yes! That's very good," I said. I had been meaning to make sure he'd been counted, but someone beat me to it. For the last year, I've been filming Arnoldo in a short documentary I'm making, called This Adventure Called California. He was labor trafficked right here in the Bay Area, and the film is following his emotional journey to recover and reconcile with his family. He lives in his truck, and it turns out that the person who helped Arnoldo with the Census was not a diligent Census worker, as I assumed, but Willis Reuter, an outreach worker for an organization called CityServe of the Tri-Valley. In addition to registering unsheltered people for the Census, CityServe provides a ton of critical services to the community --including helping people with resumes and employment searches, and assisting with housing, legal aid, and case management. In short, they provide a safety net for vulnerable people who might need food, counseling, a ride to the doctor, a job, or a shoulder to cry on. There are so many ways that our current society is failing its citizens --lack of affordable health care, housing, safe streets, quality education, trustworthy law enforcement...I could go on... so I'm grateful for organizations like CityServe who are stepping up to help.  Willis Reuter, intrepid outreach worker at CityServe of the TriValley Willis Reuter, intrepid outreach worker at CityServe of the TriValley Willis remembered that Arnoldo is a painter, and introduced him to Carol and Craig, his in-laws, who happened to need their home painted. I've been wanting more footage of Arnoldo at work, and Carol and Craig generously let me come with my camera. It turns out, they live on a ranch. A real ranch. As I packed up my gear, I got texts from Willis: "There will be goats and cows roaming around freely. And we got a new puppy, Waffles, that might greet you. Oh, also, the goats might jump on your car... And the llamas are friendly, they won't spit on you." !!!! After spending most of the pandemic in my home office, living life through screens, this was beyond exciting. Goats! Llamas! Puppies! But this is one of the greatest things about this work -- getting to enter different corners of the earth, and meet the fascinating people who live there. And in this case, dwarf Nigerian goats!  I don't think I can properly convey the cuteness, hilarity, and enthrallment of these goats. Named Rachel, Phoebe, Toast, Grits and Gravy, they were like a little pack of puppies. They were curious and unafraid of me, a new visitor, who had all kinds of tantalizing straps, cords, and cables to chew on. If I set off at a pace, they followed me. They tasted my fingers and my ponytail, and Arnoldo took a photo of a hoof print on my shoulder. (In truth, I feel like that could be a dog print too, because Waffles was super friendly as well.) And while they were uninterested in my car, the goats clearly felt very comfortable scaling Willis' vehicle, and making themselves at home. Everywhere I turned on this ranch, there was something intriguing, historic, beautiful, or thought provoking. Willis and his partner, Ariel, kindly invited me to a cookout they were having with Arnoldo that evening. Arnoldo made carne asada and charro beans, and I learned more about Willis' work. One of his projects is simply compiling a database of services available in the area, and it's been a challenge. Because of the aforementioned societal failings, a patchwork of services has developed, provided by different government agencies, nonprofits, and churches. But even identifying and navigating these services is nontrivial -- some might provide only to residents of the county, others only to minors, another to low income residents, others to seniors. So it's not always simple when members of Willis' team try to refer their clients to help. Hence, Willis' database. One thing that impresses me is that Willis goes to where the need is. He found Arnoldo in his truck, in the parking lot of a shopping plaza. I have tried to connect Arnoldo with various services since I met him, but most of them require Arnoldo to make a phone call or a visit, and some have curtailed services during the pandemic. And mostly, Arnoldo doesn't call, for all kinds of reasons. I certainly don't blame agencies for choosing how they spend their limited resources, and for expecting people to take some initiative in their own self care. But not everyone is in a position to do that. While it's exponentially more time and labor intensive to be out in the community, finding the people who have fallen through the cracks, that's exactly what Willis and CityServe are doing. When I imagine doing this work, approaching people who are living on the street or in their cars, who may have mental illnesses, be addicts, or have other issues and vulnerabilities, it seems scary, and potentially dangerous. But it doesn't faze Willis. He had a difficult childhood, with violence in his home. No child should have to live through that, but it uniquely prepared him for this work. "Sometimes, the honesty makes more sense than the plastic smiles of the corporate drones" that he left behind at his last job, he says. So often, in hearing the stories of people who've lived through trauma and violence, we think of them "overcoming" their pasts, or leaving them behind. But Willis is framing it in a different way --using his past as his secret superpower that lets him enter situations with a deeper level of understanding, resilience, and wisdom. And he says the work is therapeutic for him, too. I find this so inspiring, to think that survivors can potentially leverage their trauma into a hard-won advantage. As the traditional time for feasting and gathering is upon us, I am reminded that this year will be difficult for so many -- people who will be lonely, who won't have enough to eat, and who may not have a job as we move into a winter with more shutdowns and disease looking likely. So I'm especially grateful for people who dedicate their lives to helping those who are overlooked or forgotten, and who remind us that we can work together in very tangible ways to make life better for everyone. That was probably my last shoot with Arnoldo -- I already have a rough assembly of the documentary, and it's already too long! (Stay tuned in early 2021 for more information about it's release.) But I'm so glad I got the chance to visit this beautiful place, with people who are doing good work, and to receive the attentions of puppies and dwarf Nigerian goats. -Jennifer Huang So I am on a flight from Davao to Cebu, and going through security I had to laugh at what they would see with their x-ray vision. The current contents of my purse: 1 cooked ear of corn, bought from a bus vendor. 1 rotolight, an LED production light. 1/2 eaten bibingka, a wood-fired rice and coconut cake, bought from a bus vendor. 1 very well traveled Kind bar. 1 pack wipes. 1 pack of durian candy. Durian is the big treat here in Mindanao, but I don’t appreciate it as much as other people, so it will be a gift. 1 Sony RX-100 point and shoot camera. 1 sun hat 1 sunscreen stick, because my doc admonished me to keep applying during the day. (Very, very hard to remember, Dr. Wu!) 500 grams of Davao coffee, bought for Doug at the airport. (There’s actually more, but you get the picture. On top of that. I have my backpack with the actual video camera and very precious hard drives of footage, and then a massive duffle full of dirty clothes, tripod, light stands, and a carefully curated selection of accessories and gear.)

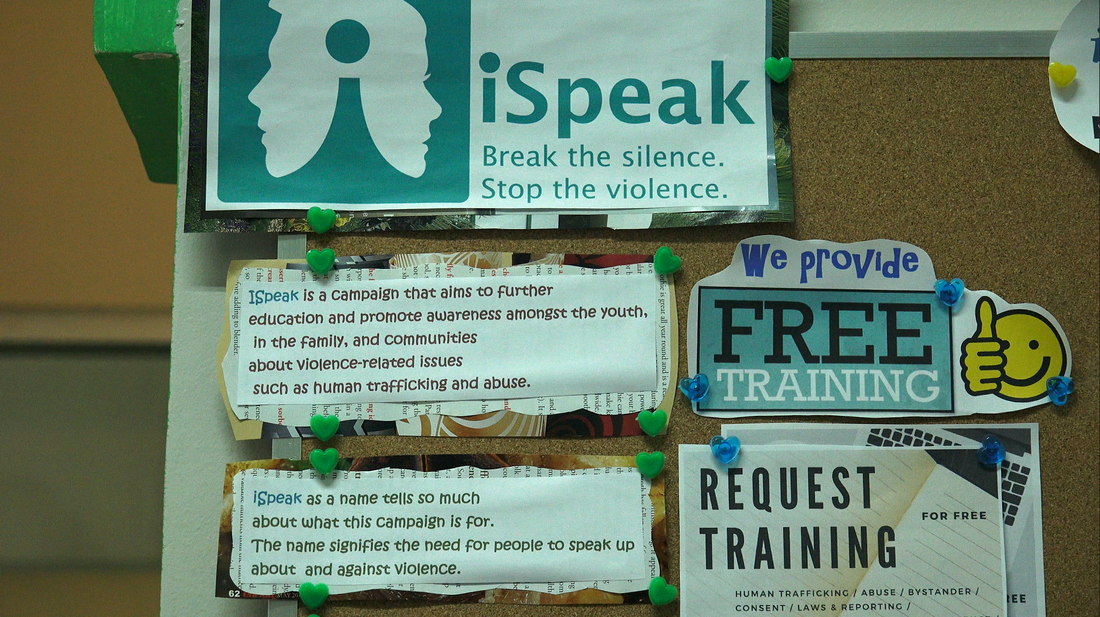

I came to Mindanao with one of the directors of My Refuge House, Rose Ann, to film her with her family on her mom’s 66th birthday. The State Department warns Americans not to come here, but I figured they should also warn us not to come to America, land of the random mass shooting. Plus everyone who has actually been here told me it was fine, and I bet the person who wrote that State Dept recommendation has not actually visited. It turns out that it is very peaceful, at least where I went, the Compostela Valley, and like everywhere else I’ve been to in the Philippines, people are friendly, curious, and eager to help and engage. I never felt remotely I danger, and as advertised, Davao (hometown of Duterte) is clean, organized, and orderly. 4 hours from Davao by bus, Rose Ann has helped her family build an amazing little community. Her parents, brother and sister all live in 3 adjacent houses, sharing meals, child rearing, looking after her parents and grandmother, and the water pump that Rose Ann had installed out back. We couldn’t go anywhere without a handful of kids or teens joining us, jumping on the back of the motorbike or running ahead of us on the paths. They were so interested in me and all of the gear I brought, in particular, the fuzzy “dead cat” — a windscreen for my microphone that turns my camera into something like a pet to them. They would literally pet it every chance they got. In the US, a lot of us relocate for our jobs, leaving our parents and families behind, and get together only for holidays or special occasions. We miss out on that ease of communal living, the cousins growing up together like siblings, the aunts and uncles involved in raising them. But it comes at a cost here, too. Rose Ann’s sister works 4 hours away. She comes home every weekend, but during the week, must leave behind her young children. Her husband must raise them —but not alone, there’s a lot of family around. She’s been doing this long distance commute for more than 15 years. So it’s a trade off. But it was great to see how close and familiar everyone was, and others in the neighborhood as well, who come to the pump and wash their clothes and dishes there, and whose kids run around like part of the family. (I’m still not sure of the provenance of some of the children, to be honest). It’s a great way of life, one that I envy and that I think we ought to consider if it could be feasible in our own lives. What's the longest you've gone without seeing the sun? For me, it was probably the time I went to a modern dance convention in a Las Vegas casino. Even away from the gambling floor, the ballrooms and buffets were disorienting in artificial light and stale air. But after 8 or 10 hours, I always escaped to the parched desert air, relieved to see the sky. Jimmy's story reminds me to never take the open air for granted. When Jimmy Lopez was twelve years old he didn't see the sun for two years, locked in a warehouse in Los Angeles. Forced by fist-and-gun wielding overseers to build furniture seven days a week, he received no pay, and if he showed any resistance, he was beaten. It sounds medieval, but it this happened in the early 2000s. I met Jimmy at the S.H.A.D.E symposium in Oakland, a survivor-led led conference focused this year on male exploitation. I can't stop thinking about his story. And so with Jimmy's permission, I share his story with you. Growing up in Honduras, gangs had tried to recruit Jimmy when he was eight. After he declined, Jimmy's whole family moved to a remote rural village, knowing that their lives were in danger. But word came that the gang hadn’t forgotten him. “They were looking to kill me,” Jimmy said. At age ten, on his own, Jimmy left home. He had no idea where he was going, but he knew he couldn't stay. Jimmy followed other children on the road and made his way, somehow, through Honduras and Mexico, all the way to the US border in Mexicali. He managed to survive by working for a family for food and a place to sleep but missed his family. “I cried every night,” A man offered to help him find a better job, and Jimmy, now twelve, jumped at the chance to make some money, and maybe even help his family. The man brought Jimmy to Los Angeles, to the furniture factory where Jimmy became a slave. Other workers would come in during the day, but Jimmy wasn't allow to speak to them. I asked if the others knew his situation. “They knew,” he said. “But they didn't say anything, because they didn't have papers.” Jimmy worked longer hours than anyone, but didn't receive a cent. “I didn't know my rights, I didn't know the culture,” he said. He didn't know that he was being trafficked, that this happened to other kids too. He continued to cry every night. One day, after a beating, Jimmy made a run for it. He got out of the warehouse and sprinted to the nearest friendly face, a man at a small food stand. The owner said he would help him. Jimmy started working at the food stand, but the man said he had a way Jimmy could make some extra money. “I just had to drive a truck to a place, and then drive a different truck back.” What could go wrong? Turns out, plenty. Jimmy was pulled over on his first trip by the police. He had no papers no license no documentation. He was 15 years old. They found 2 kilos of cocaine in the truck. Jimmy was locked up again for two years, this time in detention. He was treated as a criminal, and not recognized as the victim of child human trafficking that he was. “I ask myself, why was I brought into this world? To suffer?“ Jimmy tried to kill himself repeatedly. Jimmy finally caught a break when his court appointed lawyer recognized that Jimmy was not a hardened criminal, but a boy in need of help. The lawyer connected Jimmy to the Coalition to Abolish Slavery & Trafficking (CAST), an organization that assisted human trafficking survivors. CAST helped represent Jimmy in court, explaining to the judge what human trafficking is and how Jimmy had gotten trapped in it. Thankfully, they prevailed. Jimmy was free, but he had no home, no family, no income, no friends, and no English. There were no shelters for male trafficking survivors (even now, there are barely bed for females). Again CAST stepped in, placing Jimmy with a homeless youth program run by the Salvation Army. “I didn’t trust anyone,” Jimmy remembers. He was able to go to school and learn English, but the crying continued. Two things helped: therapy, which Jimmy was able to continue for three years after his release from prison; and peer counseling. It was another teen in this group who told him, “You can change." With her inspiration, he found the strength to keep going. CAST helped Jimmy get his T visa, specifically meant for people trafficked to this country. And thirteen years after walked away from his home in rural Honduras, Jimmy’s family came to join him in California —including a younger brother he never met. Jimmy now works at the Iberian Airlines counter in LAX. He hikes and skiis, and reads books about self-improvement. And he reads personal accounts by other survivors, which, he says, “helps me emotionally and mentally progress.” He also shares his own story as a survivor-advocate, and hopes to write his memoir one day. “What I don’t understand,” he told me,” is how people can be so bad to each other? Why can’t people help each other?“ Indeed. Jimmy’s story seems especially relevant now, with refugees fleeing gang violence from Honduras and Guatemala, searching for safety at our borders, only to be turned away with tear gas, hostility, and politically-driven lies about who they are. It also begs the question that we all should be asking about the products we buy…Who made this? Where did it come from? I was horrified to hear that furniture made in Los Angeles was the product of an exploited and abused child. I buy fair trade chocolate but it never occurred to me to seek out fair trade furniture. Many assume that products made in America couldn’t possibly include slave labor. But now we know this is incredibly naïve. I am not currently in the market for furniture, but I don’t recall ever seeing a dining room table, a couch or refrigerator that was labeled as free from slave labor. I don’t know how we as consumers can ensure that the products we have in our home are made ethically, other than only buying from local artisans whose workshops and factories we can visit ourselves. But I do know that this will never change until consumers start demanding it. One of my goals for 2019 is to upgrade my wardrobe a bit. I’m taking a pledge to only buy clothes and shoes that are fair trade or ethically made. That label is not common, and the clothes aren’t cheap. My husband asked me if this means I’m going to be making all of my own clothes. Hopefully it doesn’t come to that... but if my outfits seem kind of janky, maybe that’s why. Meanwhile, let’s all remember Jimmy, and start asking about who made the clothes, furniture, gadgets, toys and food that we bring into our homes. By Jennifer Huang Hello patient readers! Long overdue, I am finally sharing a few days from my shoot in February and March --far from comprehensive, but a snapshot of a few days. I am sorry it took me so long, most of my energy has been going to editing, grant proposals, and working with Sarah, our summer intern (more on that soon!). Truth is, I have learned in this age of social media that I am not so good at putting myself out there. So six months later, here you go! Feb 28 The sun is sparkling over the blue ocean on the horizon, birds chirp cheerfully in competing tunes, and the Girl Scouts are discussing domestic and sexual violence on the pavilion. It’s just a typical Wednesday at the compound of My Refuge House. The gardener has planted tomatoes in the beds that surround the pavilion -- the heart of the shelter where meals are eaten, Zumba is danced, meetings are held and visitors are welcomed. Most of the girls are up the hill at the original house (above left), which has been transformed into classrooms. Some of the older girls, wearing their girl scout uniforms, are doing a training with one of the ispeak advocates. iSpeak is My Refuge House's outreach and violence prevention program, providing free training on abuse and trafficking prevention for any corporation, school or organization that requests it. All of the girls I am following in The Long Rescue documentary have graduated to senior high school or college, or have been "reintegrated" back into their communities. One of the young women is actually working for iSpeak as an intern. Three others are starting families. A few of the girls that decided not to be in the film are actually going to graduate from college next year, an MRH first. March 2 It's a few days later and I am sitting in a karenderia -- a simple canteen restaurant where customers can sit down quickly with premade food and piles of white rice. Although karenderia are everything they warn travelers not to eat -- food that is precooked and then sits at room temp all day, I have found them to be better than fast food in terms of offering vegetables, and it's usually pretty salty so that's gotta have some antibacterial effect, right? I had planned to meet one of the reintegrated girls this morning here in the port on the island of Bohol and head together to her tiny island about 30 minutes offshore. But last night at 11:30 she texted to say she actually wasn't on the island but would leave early in the morning to meet me. When I asked where and when i should meet her, she replied, "just text me." Then, radio silence. So I woke up at 4 am, got onto a boat that left at 6:30, and now here I wait. In past years I might be freaking out. Is she going to show up? When? Will she be able to find me? Should I just go back to Cebu? Should I hire a boat to cross to her island? But I guess I have learned something from my years working on this film, because I am oddly calm. Whatever happens happens. It's my fifth trip shooting trip and I have seen the girls of My Refuge House grow up. Things change fast in the years between 16 and 20. I have seen some very questionable decisions and some regrets, and I have also seen hope and optimism in spite of setbacks. I've had more scheduling snafus like this than I can count or even remember, and I often think about something I realized back when working on Standing on Sacred Ground -- the cost of every minute of this film is not counted just in dollars or pesos, but in frantic sprints through airport terminals, mosquito bites and sunglasses dropped out the bus, physical therapist visits and plates of pinakbet, and most of all, tense shoulders, stomach acid, tears shed and held back as I learn more and more about the struggles these girls continue to face. That all of it could be reduced to 52 minutes seems impossible. …. 4 hours later, at 10:15 and no answered calls, I took matters into my own hands and hired a boat. Somehow I ended up on the ricketiest boat on the pier -- and that's saying something. I thought about backing out but it seemed so rude, to be like, um actually your boat doesn't look seaworthy, bye. I couldn’t bring myself to say it, though I know I should have. My fear was born out when the boat couldn't manage a crawl and the driver kept bailing buckets of water from his feet. And it was really confirmed when, on the return trip, as we pulled away, the engine suddenly cut and a lot of yelling followed. Apparently his propeller fell off. I was told that because he had waited for me for the return trip, I should now wait as he went diving for his propeller and made his repair. But I had to catch the last ferry out on the other side. So I threw money at the problem, paid the guy half of the return fare ($2) and we took off on another boat. But I’m burying the lead. I managed to find Abigail! Her phone had broke, and though we were at the pier at the same time, somehow we missed each other. Once I made to her island, I was able to see her and the new home she and her partner rent for 20 cents a day. Like other homes on the island, it’s built out over the water. Unlike other homes, the walkway to it has mostly washed away, leaving only narrow strips of wood poking at seemingly random angles to act as a makeshift bridge. I did gymnastics in high school, but these planks were less than half the width and thickness of a balance beam. Abigail crosses these many times a day, though she is pregnant. So I wasn’t about to miss seeing her home, and teetered precariously across with my camera and gear --probably not my most successful shooting (and that’s saying something) but a rather proud moment of balance accomplishment. Abigail was always considered one of the most musically talented girls when she lived at MRH, and I am hoping to use some of her original songs in the film. So I commissioned her to compose some music, and this time we went to a real recording studio, where she got to sing in front of a microphone with headphones on. She said this had been a dream since childhood that was actually coming true. Other highlights from the trip: I got bit by a dog (one of MRH’s dogs so it was rabies-free), filmed two of the staff to make make short films about them (more on this later), climbed a coconut tree, and did a drone shoot (with a drone pilot). It was also the first time my husband Doug came out to join me, and I was glad he finally got to meet all of the people I’ve been talking about for almost 4 years now.

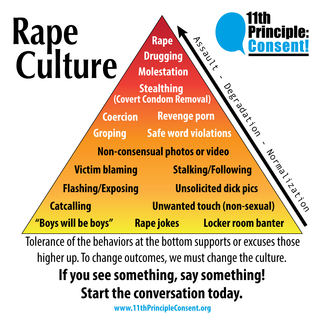

By Claire Dugan  I’m sure we have all noticed the issue of consent blowing up our headlines these days. Even before the recent Weinstein, Spacey, Louie CK, Roy Moore, Charlie Rose, and Al Franken scandals, the issue has been gaining traction for a long time. As I grew up, I learned about rape, I learned about cat-calling, I adhered to the dress code that my school imposed on girls, saw depictions of prostitutes on TV, fantasized about bondage, was fascinated by what might make me attractive to boys, and accepted the simple fact that my actions – conscious or not -- determined boys behavior. These were all separate issues for my friends and me, all part of a wide-flung web of adult knowledge that we were desperate to grasp. As part of a mindful millennial generation, we are starting to make sense of this web, tying each type of incident to the next to form an outline of respectful consent. So let’s break it down; consent is simply making sure you’re on the same page as every other party involved in your actions. It’s not only about sex, but also giving the basic respect to those around you to consider how what you want might not be what they want, and proceeding to check with them on that. It seems like what has happened as we start placing issues under the singular concept of consent, is that we begin to see all the odd adult mysteries interweave with each other; stringent gender roles beget rape culture, anti-LGBT theology begets violence, demonization of sex work begets ignorance of sex trafficking. Holding Each Other Accountable At college campuses, more reported incidents of misconduct are getting the follow up they deserve. The recent infamous Brock Turner case is a great example of this. The details surrounding this case touched on issues of class, racial inequality, misogyny, and college campus security. But especially brought to light was the prevalence of rape culture, and just how much we have to educate and learn about consent. In the video, an analogy is made between consent and a $5 bill. The analogy was attributed to twitter user Nafisa Ahmed, who said: “if you ask me for $5 and I’m too drunk to say yes or no, it’s not ok to then go take $5 out of my purse just because I didn’t say “No.” Just because I gave you $5 in the past, doesn’t mean I have to give you $5 in the future.” It’s a great, simple illustration of a framework for consent. But the analogy surprised me because it showed me how unable I was to define my own vision of consent until I heard it compared to something more tangible. Where can we start to educate? It comes down to the little things, like the notion that “boys will be boys.” Boys are taught that their very nature eludes consequence. Females, in contrast, learn passivity and acceptance of harassment. Growing up with this type of notion has the potential to snowball in some personalities into abusive behavior. But boys must be held accountable for their actions, and girls have the right not to be held accountable for the actions of males. The recent Harvey Weinstein case is a great example of this. So many people were victim to his sexual whims. There are a plethora of videos of women and men sharing their Harvey Weinstein incidents. One story I particularly remember was about a woman who said she told everyone about Weinstein’s inappropriate behavior with her, only to be told “Oh yeah, that’s Harvey” in response. In essence, his abuse was able to go on for so long because he was just a boy being a boy. Just a boy breaking into someone’s room and masturbating in front of them. Just a boy grabbing a stranger’s ass at a party. Just another boy committing rape. Just a boy using his power of people’s careers to blackmail their consent.

I have high hopes and expectations that this newish concept of consent will become common knowledge in the near future. I’m sometimes shocked, but also proud of the young people I know in high school and middle school who can have real discussions on these issues, and who know more than I did about each other’s worth. They have what would have been called in the year 2000 ‘an attitude’ about how they deserve to be treated. And even with all of the pitfalls of social media, they can curate their own reference points, newsfeeds and communities that open up so many realms of thought and perspective on self care and advocacy that they can bring to their peer groups and to their own identities. In middle school, I believed the slut-shaming I got from teachers, family members, or peers for wearing shorts or a v-neck. The generation in middle school now knows a little better than that. |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed